Artist Mohini Chandra uses photography as a tool to unpack a sense of self, rebuild connections between communities, and retrace layers of diaspora history and heritage. Focusing on photographic histories, her work explores identity and culture through the lenses of absence and migration, questioning traditional forms of documentation and how communities have been misrepresented by ‘external’ observers within anthropology and ethnography.

Q > ‘Sense of place’ through presence and absence, past and present — tell us about your travels and how these have shaped your identity.

A > I have been travelling it seems since the day I was born! Strangely enough, this was on Canvey Island and one day later, my parents moved to Gloucester and later to Australia, where I grew up. As a child I visited the Fiji-Indian diaspora community/extended family in the Pacific and more widely in America and Canada and New Zealand. While studying in London (at the Royal College of Art) I managed to get back to Fiji several times making work and eventually made it to India on an artist residency, tracing my ancestors’ journeys as indentured labourers in the late 19th Century, via the port of Kolkata to the Pacific. Thinking about it, most of my travels have been through migration with my family or through my work. My first series, as an emerging artist, was called Travels in a New World, a take on colonial and postcolonial journeys of various kinds.

Q > In what period or location have you learnt the most?

A > It’s hard to say… They are all important journeys. Probably the first journey I made as a postgraduate student, to visit my extended family around the world, researching the importance of photography in expressing narratives of diaspora experience, was pretty formative. Here, within family archives, albums and extraordinary domestic installations, I discovered the incredible history of family-run photographic studios in Fiji and started to contrast these images with earlier more colonial forms of image-making. There was an incredible freedom and fluidity in these performances of identity which belied the trauma of dislocation but also countered earlier stereotypes of the Indian migrant worker as either invisible or the exotic other. The invisibility was, I think, partly due to a kid of denial in colonial consciousness that indenture (widely used in the British Empire) was another form of slavery.

I keep returning to this important period of research, this duality, looking at colonial forms of image making, for example making work in the photographic archives of the Musee du Quai Branly in Paris, here abstracting ethnographic images from the Pacific and India.

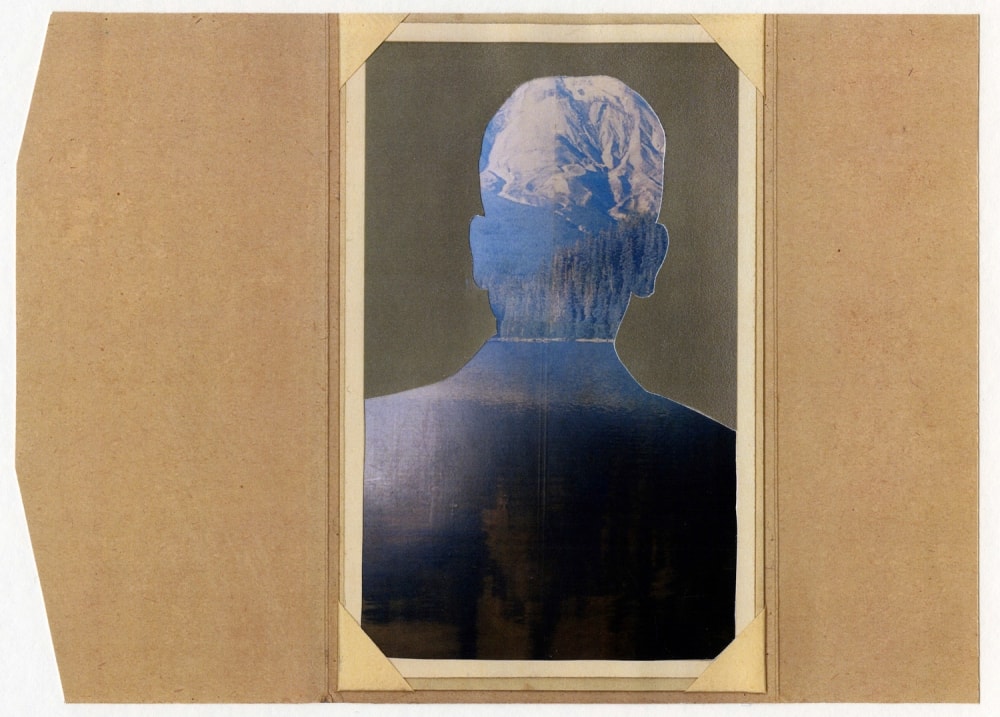

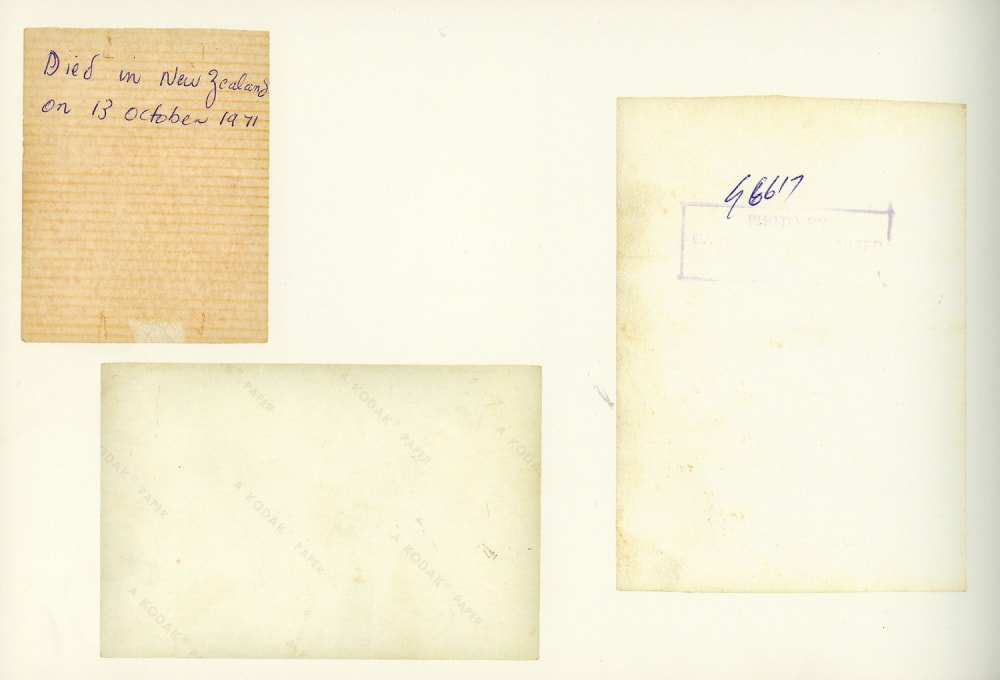

I also rework family photographs as collages as seen here in Imaginary Edens/Photos of my Father, a series that I started in 2014.

Imaginary Edens/Photos of My Father, Mohini Chandra, 2014 onwards. Background image — Matérialité, Mohini Chandra, 2017-20

Q > Unnecessary growth — things you wish hadn’t changed in your life.

A > I wish my father had not passed away a couple of years ago. He was a wonderful font of knowledge and memories of Fiji and became a frequent (if slightly bemused) collaborator in my work, narrating photographs of his youth and featuring in many films such as Travels in a New World 2.

Travels in a New World 2, (detail-moving image installation), Mohini Chandra, 1997

My film Kikau Street was made in his childhood home in Suva, Fiji which now stands empty, after the last members of the family migrated to America. This moving image installation also uses scenes from colonial era sugar plantations in Fiji (where my ancestors worked cutting cane) and a beach where an indenture ship sank — with many lives lost.

My father’s life was emblematic of the complexity of Indian post indenture experience — a kind of “double diaspora” in journeys from India to places like Fiji and then on to other locations around the world. My father was displaced and never really felt at home anywhere. Although this affected him deeply, he was, in many ways, a truly global citizen. His journeys, as a young man in the late 50s and early 60s, were in some ways groundbreaking. However, constantly challenging the cultural and racial hegemony (and prejudice) he encountered in the UK and Australia possibly took its toll on his youthful optimism and international outlook.

Kikau Street (detail from moving image), Mohini Chandra, 2016

Q > How does where you live affect your work?

A > Location is very important to me, as in many of my projects I critique but also play with notions of ethnographic “fieldwork”. I am always trying to consider alternate ways of re-telling untold histories or contemporary experiences in India, Fiji or wider diaspora communities, for example.

In recent years I moved back from a period in Australia to the UK, to take up a teaching post at Plymouth College of Art. This has been a really productive location as I have been researching and making work around shipwrecks in Plymouth — which was probably the most important port of empire, with ships such as Darwin’s Beagle and Cook’s Endeavour departing from here. Along with naval and other commercial vessels, indenture and slave ships also have passed through this port. I am working with the local archaeology team The SHIPS Project and there is a massive amount of material to study and reflect on. I have started off with a film project as part of a large cycle of works, Paradise Lost. So, after working in the Pacific and India, I am now able to investigate the very ‘heart’ of the Empire. In a way, shipwrecks point to a kind of vulnerability and permeability within the colonial project, which fascinates me. The inaugural show of Paradise Lost was delayed this summer, due to COVID, but is now scheduled for 2021 in the Gallery PCA and the next Chennai Biennale.

Paradise Lost (detail, ‘Crushed Jug’-still image), Mohini Chandra, 2020-21

Paradise Lost (detail, moving image), Mohini Chandra, 2020-21

During the recent COVID lockdowns I have been concentrating on making work in my new hometown — Totnes in Devon — which is on the River Dart, about an hour from Plymouth. Apart from its “alternative” credentials, Totnes is a classic English market town with castle, church and an interesting inland-port/merchant history. The Bengali poet, Rabindranath Tagore, spent time in residence here at the nearby Dartington Estate, which is another fascinating chapter. I am currently reflecting on this complexity, in various still and moving image works — taking Totnes as a case study for a kind of “fieldwork”.

Q > Give an example of a successful project you’ve completed — and tell us about what factors were responsible for its success.

A > There is a work I made some years ago called album pacifica, which always seems to have captured people’s imagination. In this installation of 100 images I turned photographs that I had collected from Fiji Indian diaspora families and photographic studios over, so we only see the “backs” of the images with their tell-tale studio stamps, inscriptions and signs of wear and tear. I arranged them, in a way that echoes installations I found in Fiji Indian homes. The work is a kind of “map” of diaspora and migrant experience. It’s a work that curators and audiences keep returning to and has been shown several times since being bought by the Arts Council Collection. It was also published as an artist’s book by Autograph. Most recently it was shown in the Courtauld Institute’s exhibition Unquiet Moments: Capturing the Everyday (shown here). I think it’s a work that tells a story through little clues and perhaps surprises an audience. It also speaks of photographic history and the role of photography within the family, which I think/hope we can all relate to.

album pacifica, publication, Mohini Chandra, 1996-97 (Courtesy of Autograph)

Q > Who or what inspires you?

A > So many things! In terms of art, montage and political art as well as conceptual art. The array of contemporary globalised art practices which have increasingly looked at issues of identity in evermore sophisticated ways.

Q > From global interactions to local resistances — which topics should we be discussing more?

A > Well, the BLM movement has raised some critical issues at a critical time. It’s not that these things weren’t being said before, but the world is finally paying attention. We cannot understand racism and prejudice without understanding the power relationships, economic iniquities and cultural “othering” put into place by colonialism and empire — the origins of global capitalism — which we live with today. Therefore, this process of decolonisation, which art and education (the fields I am invested in) have a big part to play in, is absolutely essential.

Q > Which things do you think the people around you often take for granted?

A > I think after COVID, we are learning not to take anything for granted. That suddenly our sense of security and comfort is not as safe as we thought, in the West. In that sense we have become more aware that we are part of a global whole — facing a very big set of interlinked problems that include everything from sustainability to inequality and prejudice.

Since graduating from the Royal College of Art, Chandra has exhibited widely, including: Paradise Now? Contemporary Art From the Pacific, Asia Society Museum, New York; Out of India, Queens Museum of Art, New York; The East Wing Collection, Courtauld Institute, London; Crown Jewels, Neue Gesellschaft Fur Bildende Kunst (NGBK) Berlin & Kampnagel Art Gallery, Hamburg; 000ZeroZeroZero, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London; Artist and the Archive, Shoreditch Biennale; and in international events such as the First Johannesburg Biennale and the Photography Triennial — Dislocations, Rovaniemi Museum in Finland. She has had solo shows at venues such as the Southeast Museum of Photography, Florida and the Bluecoat Gallery, Liverpool. Most recently, Chandra exhibited in Photo Kathmandu (2015), CCP Declares at the Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne (2016), Now! Now! In more than one place, curated by Sonia Boyce in collaboration with Black Artists and Modernism (BAM) research project/conference at Tate Modern, Chelsea College of Arts-University of the Arts London (2016), Confusion of Tongues: Art and the Limits of Language, The Courtauld Gallery, Somerset House, London (2016), the Focus Festival of Photography in Mumbai, (2017) and the Third Oceanic Performance Biennale in Auckland (2017).